In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to create Storm topologies and deploy them to a Storm cluster. Java will be the main language used, but a few examples will use Python to illustrate Storm’s multi-language capabilities.

This tutorial uses examples from the storm-starter project. It’s recommended that you clone the project and follow along with the examples. Read Setting up a development environment and Creating a new Storm project to get your machine set up.

A Storm cluster is superficially similar to a Hadoop cluster. Whereas on Hadoop you run “MapReduce jobs”, on Storm you run “topologies”. “Jobs” and “topologies” themselves are very different – one key difference is that a MapReduce job eventually finishes, whereas a topology processes messages forever (or until you kill it).

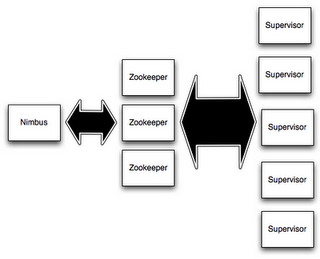

There are two kinds of nodes on a Storm cluster: the master node and the worker nodes. The master node runs a daemon called “Nimbus” that is similar to Hadoop’s “JobTracker”. Nimbus is responsible for distributing code around the cluster, assigning tasks to machines, and monitoring for failures.

Each worker node runs a daemon called the “Supervisor”. The supervisor listens for work assigned to its machine and starts and stops worker processes as necessary based on what Nimbus has assigned to it. Each worker process executes a subset of a topology; a running topology consists of many worker processes spread across many machines.

All coordination between Nimbus and the Supervisors is done through a Zookeeper cluster. Additionally, the Nimbus daemon and Supervisor daemons are fail-fast and stateless; all state is kept in Zookeeper or on local disk. This means you can kill -9 Nimbus or the Supervisors and they’ll start back up like nothing happened. This design leads to Storm clusters being incredibly stable.

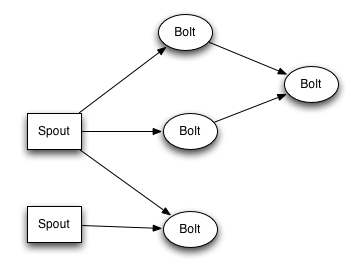

To do realtime computation on Storm, you create what are called “topologies”. A topology is a graph of computation. Each node in a topology contains processing logic, and links between nodes indicate how data should be passed around between nodes.

Running a topology is straightforward. First, you package all your code and dependencies into a single jar. Then, you run a command like the following:

storm jar all-my-code.jar org.apache.storm.MyTopology arg1 arg2

This runs the class org.apache.storm.MyTopology with the arguments arg1 and arg2. The main function of the class defines the topology and submits it to Nimbus. The storm jar part takes care of connecting to Nimbus and uploading the jar.

Since topology definitions are just Thrift structs, and Nimbus is a Thrift service, you can create and submit topologies using any programming language. The above example is the easiest way to do it from a JVM-based language. See Running topologies on a production cluster] for more information on starting and stopping topologies.

The core abstraction in Storm is the “stream”. A stream is an unbounded sequence of tuples. Storm provides the primitives for transforming a stream into a new stream in a distributed and reliable way. For example, you may transform a stream of tweets into a stream of trending topics.

The basic primitives Storm provides for doing stream transformations are “spouts” and “bolts”. Spouts and bolts have interfaces that you implement to run your application-specific logic.

A spout is a source of streams. For example, a spout may read tuples off of a Kestrel queue and emit them as a stream. Or a spout may connect to the Twitter API and emit a stream of tweets.

A bolt consumes any number of input streams, does some processing, and possibly emits new streams. Complex stream transformations, like computing a stream of trending topics from a stream of tweets, require multiple steps and thus multiple bolts. Bolts can do anything from run functions, filter tuples, do streaming aggregations, do streaming joins, talk to databases, and more.

Networks of spouts and bolts are packaged into a “topology” which is the top-level abstraction that you submit to Storm clusters for execution. A topology is a graph of stream transformations where each node is a spout or bolt. Edges in the graph indicate which bolts are subscribing to which streams. When a spout or bolt emits a tuple to a stream, it sends the tuple to every bolt that subscribed to that stream.

Links between nodes in your topology indicate how tuples should be passed around. For example, if there is a link between Spout A and Bolt B, a link from Spout A to Bolt C, and a link from Bolt B to Bolt C, then everytime Spout A emits a tuple, it will send the tuple to both Bolt B and Bolt C. All of Bolt B’s output tuples will go to Bolt C as well.

Each node in a Storm topology executes in parallel. In your topology, you can specify how much parallelism you want for each node, and then Storm will spawn that number of threads across the cluster to do the execution.

A topology runs forever, or until you kill it. Storm will automatically reassign any failed tasks. Additionally, Storm guarantees that there will be no data loss, even if machines go down and messages are dropped.

Storm uses tuples as its data model. A tuple is a named list of values, and a field in a tuple can be an object of any type. Out of the box, Storm supports all the primitive types, strings, and byte arrays as tuple field values. To use an object of another type, you just need to implement a serializer for the type.

Every node in a topology must declare the output fields for the tuples it emits. For example, this bolt declares that it emits 2-tuples with the fields “double” and “triple”:

public class DoubleAndTripleBolt extends BaseRichBolt {

private OutputCollectorBase _collector;

@Override

public void prepare(Map conf, TopologyContext context, OutputCollectorBase collector) {

_collector = collector;

}

@Override

public void execute(Tuple input) {

int val = input.getInteger(0);

_collector.emit(input, new Values(val*2, val*3));

_collector.ack(input);

}

@Override

public void declareOutputFields(OutputFieldsDeclarer declarer) {

declarer.declare(new Fields("double", "triple"));

}

}

The declareOutputFields function declares the output fields ["double", "triple"] for the component. The rest of the bolt will be explained in the upcoming sections.

Let’s take a look at a simple topology to explore the concepts more and see how the code shapes up. Let’s look at the ExclamationTopology definition from storm-starter:

TopologyBuilder builder = new TopologyBuilder();

builder.setSpout("words", new TestWordSpout(), 10);

builder.setBolt("exclaim1", new ExclamationBolt(), 3)

.shuffleGrouping("words");

builder.setBolt("exclaim2", new ExclamationBolt(), 2)

.shuffleGrouping("exclaim1");

This topology contains a spout and two bolts. The spout emits words, and each bolt appends the string “!!!” to its input. The nodes are arranged in a line: the spout emits to the first bolt which then emits to the second bolt. If the spout emits the tuples [“bob”] and [“john”], then the second bolt will emit the words [“bob!!!!!!”] and [“john!!!!!!”].

This code defines the nodes using the setSpout and setBolt methods. These methods take as input a user-specified id, an object containing the processing logic, and the amount of parallelism you want for the node. In this example, the spout is given id “words” and the bolts are given ids “exclaim1” and “exclaim2”.

The object containing the processing logic implements the IRichSpout interface for spouts and the IRichBolt interface for bolts.

The last parameter, how much parallelism you want for the node, is optional. It indicates how many threads should execute that component across the cluster. If you omit it, Storm will only allocate one thread for that node.

setBolt returns an InputDeclarer object that is used to define the inputs to the Bolt. Here, component “exclaim1” declares that it wants to read all the tuples emitted by component “words” using a shuffle grouping, and component “exclaim2” declares that it wants to read all the tuples emitted by component “exclaim1” using a shuffle grouping. “shuffle grouping” means that tuples should be randomly distributed from the input tasks to the bolt’s tasks. There are many ways to group data between components. These will be explained in a few sections.

If you wanted component “exclaim2” to read all the tuples emitted by both component “words” and component “exclaim1”, you would write component “exclaim2”’s definition like this:

builder.setBolt("exclaim2", new ExclamationBolt(), 5)

.shuffleGrouping("words")

.shuffleGrouping("exclaim1");

As you can see, input declarations can be chained to specify multiple sources for the Bolt.

Let’s dig into the implementations of the spouts and bolts in this topology. Spouts are responsible for emitting new messages into the topology. TestWordSpout in this topology emits a random word from the list [“nathan”, “mike”, “jackson”, “golda”, “bertels”] as a 1-tuple every 100ms. The implementation of nextTuple() in TestWordSpout looks like this:

public void nextTuple() {

Utils.sleep(100);

final String[] words = new String[] {"nathan", "mike", "jackson", "golda", "bertels"};

final Random rand = new Random();

final String word = words[rand.nextInt(words.length)];

_collector.emit(new Values(word));

}

As you can see, the implementation is very straightforward.

ExclamationBolt appends the string “!!!” to its input. Let’s take a look at the full implementation for ExclamationBolt:

public static class ExclamationBolt implements IRichBolt {

OutputCollector _collector;

@Override

public void prepare(Map conf, TopologyContext context, OutputCollector collector) {

_collector = collector;

}

@Override

public void execute(Tuple tuple) {

_collector.emit(tuple, new Values(tuple.getString(0) + "!!!"));

_collector.ack(tuple);

}

@Override

public void cleanup() {

}

@Override

public void declareOutputFields(OutputFieldsDeclarer declarer) {

declarer.declare(new Fields("word"));

}

@Override

public Map<String, Object> getComponentConfiguration() {

return null;

}

}

The prepare method provides the bolt with an OutputCollector that is used for emitting tuples from this bolt. Tuples can be emitted at anytime from the bolt – in the prepare, execute, or cleanup methods, or even asynchronously in another thread. This prepare implementation simply saves the OutputCollector as an instance variable to be used later on in the execute method.

The execute method receives a tuple from one of the bolt’s inputs. The ExclamationBolt grabs the first field from the tuple and emits a new tuple with the string “!!!” appended to it. If you implement a bolt that subscribes to multiple input sources, you can find out which component the Tuple came from by using the Tuple#getSourceComponent method.

There’s a few other things going on in the execute method, namely that the input tuple is passed as the first argument to emit and the input tuple is acked on the final line. These are part of Storm’s reliability API for guaranteeing no data loss and will be explained later in this tutorial.

The cleanup method is called when a Bolt is being shutdown and should cleanup any resources that were opened. There’s no guarantee that this method will be called on the cluster: for example, if the machine the task is running on blows up, there’s no way to invoke the method. The cleanup method is intended for when you run topologies in local mode (where a Storm cluster is simulated in process), and you want to be able to run and kill many topologies without suffering any resource leaks.

The declareOutputFields method declares that the ExclamationBolt emits 1-tuples with one field called “word”.

The getComponentConfiguration method allows you to configure various aspects of how this component runs. This is a more advanced topic that is explained further on Configuration.

Methods like cleanup and getComponentConfiguration are often not needed in a bolt implementation. You can define bolts more succinctly by using a base class that provides default implementations where appropriate. ExclamationBolt can be written more succinctly by extending BaseRichBolt, like so:

public static class ExclamationBolt extends BaseRichBolt {

OutputCollector _collector;

@Override

public void prepare(Map conf, TopologyContext context, OutputCollector collector) {

_collector = collector;

}

@Override

public void execute(Tuple tuple) {

_collector.emit(tuple, new Values(tuple.getString(0) + "!!!"));

_collector.ack(tuple);

}

@Override

public void declareOutputFields(OutputFieldsDeclarer declarer) {

declarer.declare(new Fields("word"));

}

}

Let’s see how to run the ExclamationTopology in local mode and see that it’s working.

Storm has two modes of operation: local mode and distributed mode. In local mode, Storm executes completely in process by simulating worker nodes with threads. Local mode is useful for testing and development of topologies. You can read more about running topologies in local mode on Local mode.

To run a topology in local mode run the command storm local instead of storm jar.

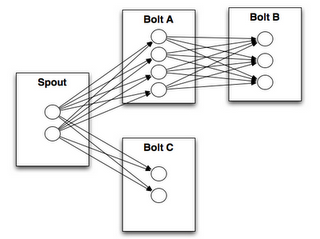

A stream grouping tells a topology how to send tuples between two components. Remember, spouts and bolts execute in parallel as many tasks across the cluster. If you look at how a topology is executing at the task level, it looks something like this:

When a task for Bolt A emits a tuple to Bolt B, which task should it send the tuple to?

A “stream grouping” answers this question by telling Storm how to send tuples between sets of tasks. Before we dig into the different kinds of stream groupings, let’s take a look at another topology from storm-starter. This WordCountTopology reads sentences off of a spout and streams out of WordCountBolt the total number of times it has seen that word before:

TopologyBuilder builder = new TopologyBuilder();

builder.setSpout("sentences", new RandomSentenceSpout(), 5);

builder.setBolt("split", new SplitSentence(), 8)

.shuffleGrouping("sentences");

builder.setBolt("count", new WordCount(), 12)

.fieldsGrouping("split", new Fields("word"));

SplitSentence emits a tuple for each word in each sentence it receives, and WordCount keeps a map in memory from word to count. Each time WordCount receives a word, it updates its state and emits the new word count.

There’s a few different kinds of stream groupings.

The simplest kind of grouping is called a “shuffle grouping” which sends the tuple to a random task. A shuffle grouping is used in the WordCountTopology to send tuples from RandomSentenceSpout to the SplitSentence bolt. It has the effect of evenly distributing the work of processing the tuples across all of SplitSentence bolt’s tasks.

A more interesting kind of grouping is the “fields grouping”. A fields grouping is used between the SplitSentence bolt and the WordCount bolt. It is critical for the functioning of the WordCount bolt that the same word always go to the same task. Otherwise, more than one task will see the same word, and they’ll each emit incorrect values for the count since each has incomplete information. A fields grouping lets you group a stream by a subset of its fields. This causes equal values for that subset of fields to go to the same task. Since WordCount subscribes to SplitSentence’s output stream using a fields grouping on the “word” field, the same word always goes to the same task and the bolt produces the correct output.

Fields groupings are the basis of implementing streaming joins and streaming aggregations as well as a plethora of other use cases. Underneath the hood, fields groupings are implemented using mod hashing.

There’s a few other kinds of stream groupings. You can read more about them on Concepts.

Bolts can be defined in any language. Bolts written in another language are executed as subprocesses, and Storm communicates with those subprocesses with JSON messages over stdin/stdout. The communication protocol just requires an ~100 line adapter library, and Storm ships with adapter libraries for Ruby, Python, and Fancy.

Here’s the definition of the SplitSentence bolt from WordCountTopology:

public static class SplitSentence extends ShellBolt implements IRichBolt {

public SplitSentence() {

super("python", "splitsentence.py");

}

public void declareOutputFields(OutputFieldsDeclarer declarer) {

declarer.declare(new Fields("word"));

}

}

SplitSentence overrides ShellBolt and declares it as running using python with the arguments splitsentence.py. Here’s the implementation of splitsentence.py:

import storm

class SplitSentenceBolt(storm.BasicBolt):

def process(self, tup):

words = tup.values[0].split(" ")

for word in words:

storm.emit([word])

SplitSentenceBolt().run()

For more information on writing spouts and bolts in other languages, and to learn about how to create topologies in other languages (and avoid the JVM completely), see Using non-JVM languages with Storm.

Earlier on in this tutorial, we skipped over a few aspects of how tuples are emitted. Those aspects were part of Storm’s reliability API: how Storm guarantees that every message coming off a spout will be fully processed. See Guaranteeing message processing for information on how this works and what you have to do as a user to take advantage of Storm’s reliability capabilities.

Storm guarantees that every message will be played through the topology at least once. A common question asked is “how do you do things like counting on top of Storm? Won’t you overcount?” Storm has a higher level API called Trudent that let you achieve exactly-once messaging semantics for most computations. Read more about Trident here.

This tutorial showed how to do basic stream processing on top of Storm. There’s lots more things you can do with Storm’s primitives. One of the most interesting applications of Storm is Distributed RPC, where you parallelize the computation of intense functions on the fly. Read more about Distributed RPC here.

This tutorial gave a broad overview of developing, testing, and deploying Storm topologies. The rest of the documentation dives deeper into all the aspects of using Storm.